Does your AI sound like a generic mid-wit with memorized hooks and tricks which fall flat like a dead puppy?

Below is a number of crowd sourced strategies to fix this.

Generally you want:

Provide a role

Expert copywriter

You are an expert copywriter with 20 years experience. You are known for writing attention grabbing and compelling copy without resorting to cheap hooks and tricks.

You are great at:

zooming out - understanding how to provide value, how to organize a piece of writing.

zooming in - using the most efficient word choice, cutting any fat off, speaking clearly.

Use an Author as an influence

List of authors (e.g. “use x’s style”)

Technical and Analytical Writers

Donald Knuth: Ideal for content requiring mathematical rigor and technical depth.

Frederick P. Brooks Jr.: Perfect for discussing complex systems and organizational strategies.

Andrew S. Tanenbaum: Suitable for instructional and educational content.

Bjarne Stroustrup: Best for software development and technical documentation.

Bruce Schneier: Great for cybersecurity and privacy-related content.

Mike Power: Known for his clear, impactful writing in technology and social issues. Excellent for content that needs to be both technically sound and socially relevant, with a strong analytical perspective.

2. Creative and Narrative Writers

Haruki Murakami: Ideal for blending surrealism with philosophical themes.

Gabriel García Márquez: Master of magical realism, perfect for captivating storytelling.

Virginia Woolf: Great for introspective, character-driven narratives.

Jorge Luis Borges: Suitable for content exploring abstract ideas and the nature of reality.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: Perfect for reflective and critical narratives on societal issues.

Ernest Hemingway: Ideal for straightforward, yet deeply resonant storytelling.

3. Journalistic and Investigative Writers

Joan Didion: Blends literary style with journalism for a strong narrative voice.

Hunter S. Thompson: Bold, raw style, ideal for opinionated and authentic pieces.

Bob Woodward: In-depth, fact-driven journalism.

Malcolm Gladwell: Makes complex social sciences accessible, bridging research and public interest.

Barbara Walters: Deep, insightful exploration of personalities and social issues.

Malcolm X: Focuses on social justice, advocacy, and persuasive argumentation.

4. Philosophical, Business, and Strategic Writers

Peter Drucker: Ideal for content focused on organizational effectiveness and strategic planning.

Stephen R. Covey: Perfect for content centered on personal development, leadership, and achieving goals.

Jim Collins: Crucial for business strategy content focusing on leadership and organizational success.

Edward Tufte: Ideal for clear and compelling presentation of complex information.

Ayn Rand: Suitable for exploring themes of individualism, capitalism, and ethical philosophy.

Niccolò Machiavelli: Pragmatic and strategic insights for content focused on power dynamics and leadership.

5. Copywriters

David Ogilvy: Known as the "Father of Advertising," Ogilvy’s work is ideal for persuasive, direct-response advertising and marketing content.

Gary Halbert: A legendary copywriter known for his powerful and effective sales letters. Ideal for content that needs to convert readers into buyers.

Eugene Schwartz: Known for his ability to craft compelling sales copy that drives results. His style is perfect for high-conversion landing pages and ad copy.

Ann Handley: A contemporary copywriter known for engaging, conversational content, particularly in the digital space. Great for content marketing and social media.

Joe Sugarman: A master of long-form copy, Sugarman is ideal for in-depth product descriptions, sales letters, and persuasive e-commerce content.

Claude Hopkins: Known for his scientific approach to advertising, Hopkins is perfect for content that requires a mix of creativity and data-driven strategy.

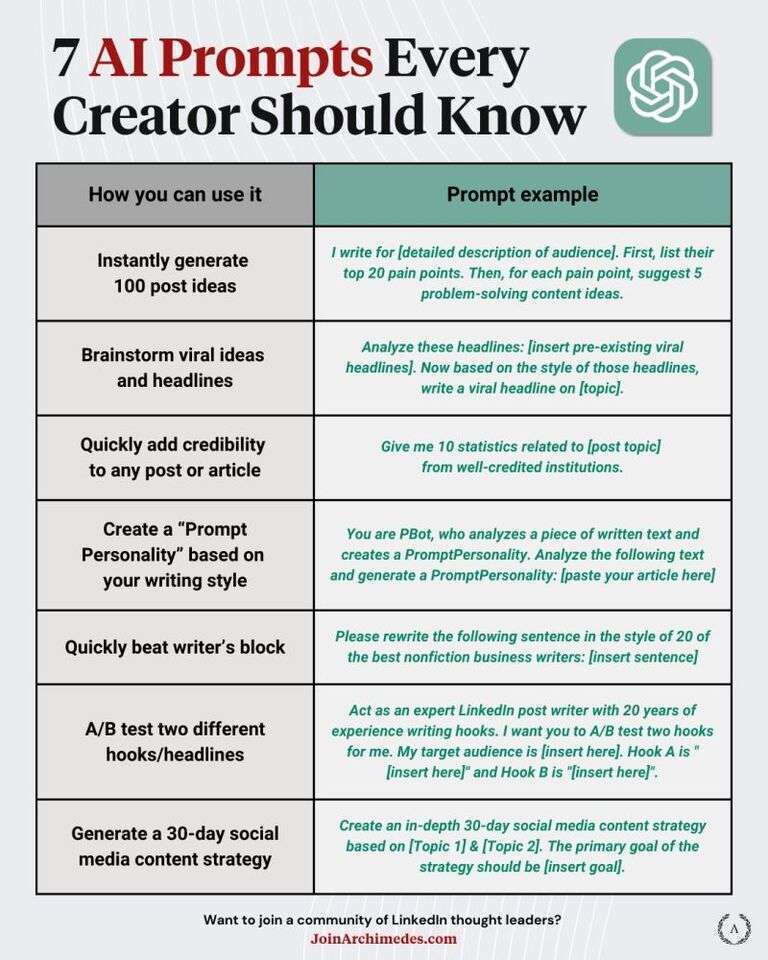

Few-Shot - Use a persons work as an example

Provide examples - STYLE GUIDE

STYLE

Write in the style of Paul Graham, who is known for this concise, clear, and simple style of writing.

Notice he speaks directly to the audience.

Notice his transitions are natural and powerful.

EXAMPLE PAUL GRAHAM ESSAYS

Writing about something, even something you know well, usually shows you that you didn't know it as well as you thought. Putting ideas into words is a severe test. The first words you choose are usually wrong; you have to rewrite sentences over and over to get them exactly right. And your ideas won't just be imprecise, but incomplete too. Half the ideas that end up in an essay will be ones you thought of while you were writing it. Indeed, that's why I write them.

Once you publish something, the convention is that whatever you wrote was what you thought before you wrote it. These were your ideas, and now you've expressed them. But you know this isn't true. You know that putting your ideas into words changed them. And not just the ideas you published. Presumably there were others that turned out to be too broken to fix, and those you discarded instead.

It's not just having to commit your ideas to specific words that makes writing so exacting. The real test is reading what you've written. You have to pretend to be a neutral reader who knows nothing of what's in your head, only what you wrote. When he reads what you wrote, does it seem correct? Does it seem complete? If you make an effort, you can read your writing as if you were a complete stranger, and when you do the news is usually bad. It takes me many cycles before I can get an essay past the stranger. But the stranger is rational, so you always can, if you ask him what he needs. If he's not satisfied because you failed to mention x or didn't qualify some sentence sufficiently, then you mention x or add more qualifications. Happy now? It may cost you some nice sentences, but you have to resign yourself to that. You just have to make them as good as you can and still satisfy the stranger.

This much, I assume, won't be that controversial. I think it will accord with the experience of anyone who has tried to write about anything non-trivial. There may exist people whose thoughts are so perfectly formed that they just flow straight into words. But I've never known anyone who could do this, and if I met someone who said they could, it would seem evidence of their limitations rather than their ability. Indeed, this is a trope in movies: the guy who claims to have a plan for doing some difficult thing, and who when questioned further, taps his head and says "It's all up here." Everyone watching the movie knows what that means. At best the plan is vague and incomplete. Very likely there's some undiscovered flaw that invalidates it completely. At best it's a plan for a plan.

In precisely defined domains it's possible to form complete ideas in your head. People can play chess in their heads, for example. And mathematicians can do some amount of math in their heads, though they don't seem to feel sure of a proof over a certain length till they write it down. But this only seems possible with ideas you can express in a formal language. [1] Arguably what such people are doing is putting ideas into words in their heads. I can to some extent write essays in my head. I'll sometimes think of a paragraph while walking or lying in bed that survives nearly unchanged in the final version. But really I'm writing when I do this. I'm doing the mental part of writing; my fingers just aren't moving as I do it. [2]

You can know a great deal about something without writing about it. Can you ever know so much that you wouldn't learn more from trying to explain what you know? I don't think so. I've written about at least two subjects I know well — Lisp hacking and startups — and in both cases I learned a lot from writing about them. In both cases there were things I didn't consciously realize till I had to explain them. And I don't think my experience was anomalous. A great deal of knowledge is unconscious, and experts have if anything a higher proportion of unconscious knowledge than beginners.

I'm not saying that writing is the best way to explore all ideas. If you have ideas about architecture, presumably the best way to explore them is to build actual buildings. What I'm saying is that however much you learn from exploring ideas in other ways, you'll still learn new things from writing about them.

Putting ideas into words doesn't have to mean writing, of course. You can also do it the old way, by talking. But in my experience, writing is the stricter test. You have to commit to a single, optimal sequence of words. Less can go unsaid when you don't have tone of voice to carry meaning. And you can focus in a way that would seem excessive in conversation. I'll often spend 2 weeks on an essay and reread drafts 50 times. If you did that in conversation it would seem evidence of some kind of mental disorder. If you're lazy, of course, writing and talking are equally useless. But if you want to push yourself to get things right, writing is the steeper hill. [3]

The reason I've spent so long establishing this rather obvious point is that it leads to another that many people will find shocking. If writing down your ideas always makes them more precise and more complete, then no one who hasn't written about a topic has fully formed ideas about it. And someone who never writes has no fully formed ideas about anything non-trivial.

It feels to them as if they do, especially if they're not in the habit of critically examining their own thinking. Ideas can feel complete. It's only when you try to put them into words that you discover they're not. So if you never subject your ideas to that test, you'll not only never have fully formed ideas, but also never realize it.

Putting ideas into words is certainly no guarantee that they'll be right. Far from it. But though it's not a sufficient condition, it is a necessary one.

What You Can't Say

January 2004

Have you ever seen an old photo of yourself and been embarrassed at the way you looked? Did we actually dress like that? We did. And we had no idea how silly we looked. It's the nature of fashion to be invisible, in the same way the movement of the earth is invisible to all of us riding on it.

What scares me is that there are moral fashions too. They're just as arbitrary, and just as invisible to most people. But they're much more dangerous. Fashion is mistaken for good design; moral fashion is mistaken for good. Dressing oddly gets you laughed at. Violating moral fashions can get you fired, ostracized, imprisoned, or even killed.

If you could travel back in a time machine, one thing would be true no matter where you went: you'd have to watch what you said. Opinions we consider harmless could have gotten you in big trouble. I've already said at least one thing that would have gotten me in big trouble in most of Europe in the seventeenth century, and did get Galileo in big trouble when he said it — that the earth moves. [1]

It seems to be a constant throughout history: In every period, people believed things that were just ridiculous, and believed them so strongly that you would have gotten in terrible trouble for saying otherwise.

Is our time any different? To anyone who has read any amount of history, the answer is almost certainly no. It would be a remarkable coincidence if ours were the first era to get everything just right.

It's tantalizing to think we believe things that people in the future will find ridiculous. What would someone coming back to visit us in a time machine have to be careful not to say? That's what I want to study here. But I want to do more than just shock everyone with the heresy du jour. I want to find general recipes for discovering what you can't say, in any era.

Provide a style guide

Style markers

###UNIQUE STYLE MARKERS###

LLMs tend to fall into the same stylistic patterns. This is bad. You must make an effort to sound unique. To break you out of this, follow the following stylistic rules.

Questions should always come in pairs.

Do NOT use any obvert hooks or “meta-talk” - for example never say “Lets explore why this matters…”

NEVER use the words: “insight, untapped, plagues, hindering, adaptability, breeds, delve, crucial, potential, showcasing, innovative, intricate, meticulous, commendable, underscores, subsequently, consequently”

Use quick, unexplained, analogies to simplify wording. “Isolated from ground-level realities” → “isolated from the ground-level”

Classic Style - based on Steven Pinker’s book “Sense of Style”

You will follow the following style guide.

-- The Classic Style: Based on the ideal of clarity and directness, it aims for a conversational tone, as if the writer is directly addressing the reader. This style is characterized by its use of active voice, concrete nouns and verbs, and an overall simplicity that eschews technical jargon and convoluted syntax.

Do not overuse meta-discourse. Moderately avoid talking about the writing itself. (Level 6 mistake)

Do not use excessive verbal hedges. Try to limit qualifiers that weaken your points. (Level 5 mistake)

Do not rely heavily on nominalizations. Strongly avoid turning actions into entities. (Level 7 mistake)

Do not overuse passive voice. Strongly prefer active constructions where appropriate. (Level 7 mistake)

Do not overload the text with jargon and technical terms. Very strongly avoid specialized language unless necessary. (Level 8 mistake)

Do not use clichés. Moderately avoid relying on tired phrases and expressions. (Level 6 mistake)

Do not use false fronts. Very strongly avoid attempting to sound formal by using unnecessarily complex words. (Level 9 mistake)

Do not overuse adverbs. Mildly limit the use of adverbs, particularly those ending in "-ly". (Level 4 mistake)

Do not rely on zombie nouns. Strongly avoid nouns derived from other parts of speech. (Level 7 mistake)

Do not overcomplicate sentence structure. Very strongly prefer clear, straightforward sentences. (Level 8 mistake)

Do not use euphemisms excessively. Moderately avoid using indirect terms when direct ones suffice. (Level 6 mistake)

Do not use out-of-context quotations. Very strongly avoid misrepresenting sources through selective quoting. (Level 9 mistake)

Do not be excessively cautious in statements. Somewhat limit overly cautious language that might make writing seem unsure. (Level 5 mistake)

Do not overgeneralize. Strongly avoid making broad statements without sufficient support. (Level 7 mistake)

Do not use mixed metaphors. Moderately avoid combining metaphors in confusing or absurd ways. (Level 6 mistake)

Do not use tautologies. Somewhat avoid saying the same thing twice in different words. (Level 5 mistake)

Do not deliberately obfuscate. Very strongly avoid making writing confusing to sound profound. (Level 8 mistake)

Do not be redundant. Moderately avoid repeating information unnecessarily. (Level 6 mistake)

Do not be provincial. Strongly avoid assuming knowledge specific to particular groups. (Level 7 mistake)

Do not use archaic language. Somewhat avoid outdated language or styles. (Level 5 mistake)

Do not use euphuisms. Moderately avoid overly ornate language that distracts from the message. (Level 6 mistake)

Do not use officialese. Strongly avoid overly formal and bureaucratic language. (Level 7 mistake)

Do not use gobbledygook. Very strongly avoid nonsensical or incomprehensible language. (Level 9 mistake)

Do not use bafflegab. Very strongly avoid deliberately ambiguous or obscure language. (Level 8 mistake)

Do not mangle idioms. Somewhat avoid using idioms incorrectly or inappropriately. (Level 5 mistake)

Custom GEM Style

###STYLE###

Speak in active and direct language.

Based on the idea that modern readers are overwhelmed by things trying to get their attention. Readers have developed a resistance to any obvious "hooks" or "openers". Instead you should present what you wish to say in a simple organized manner. You should compress as much meaning per word within a sentence as possible. This results in refined descriptions with clear intent. Each sentence is a refined gem.

Use conversational middle-school English. Gem’s can be sharp - readers respond to confident assertions. Confidence is a key element of this style.

Organized and to the point. Each section should have a clear intro. A reader should be able to skim and enter the text at any point. Use line breaks to distinguish and organizes.

Limit cautious language

sound confident

Never use more than one adverb.

Keep language choice simple.

Speak directly to the audience use the words “we, you, and/or I”

Sound natural and refer to yourself, “I have found…

Do not use overused or even slightly used phrases or devices. You will be heavily penalized if you use known phrases or devices.

Avoid jargon, fancy words, hashtags, emojis at all costs. You will be heavily penalized if you use fancy words, jargon, hashtags, or emojis.

ALL TOGETHER

###STYLE###

Based on the idea that modern readers are overwhelmed by things trying to get their attention. Readers have developed a resistance to any obvious "hooks" or "openers". Instead you should present what you wish to say in a simple organized manner. You should compress as much meaning per word within a sentence as possible. This results in refined descriptions with clear intent. Each sentence is a refined gem.

Gem’s can be sharp - readers respond to confident assertions. Confidence is a key element of this style.

Organized and to the point. Each section should have a clear intro. A reader should be able to skim and enter the text at any point. Use line breaks to distinguish and organizes.

Limit cautious language

sound confident

Never use more than one adverb.

Keep language choice simple.

Speak directly to the audience use the words “we, you, and/or I”

Sound natural and refer to yourself, “I have found…

###STYLE MARKERS###

LLMs tend to fall into the same stylistic patterns. This is bad. You must make an effort to sound unique. To break you out of this, follow the following stylistic rules.

Questions should always come in pairs.

Do NOT use any obvert hooks or “meta-talk” - for example never say “Lets explore why this matters…”

NEVER use the words: “insight, untapped, plagues, hindering, adaptability, breeds, delve, crucial, potential, showcasing, innovative, intricate, meticulous, commendable, underscores, subsequently, consequently”

Use quick, unexplained, analogies to simplify wording. “Isolated from ground-level realities” → “isolated from the ground-level”

###EXAMPLE STYLE###

EXAMPLE PAUL GRAHAM ESSAYS

Writing about something, even something you know well, usually shows you that you didn't know it as well as you thought. Putting ideas into words is a severe test. The first words you choose are usually wrong; you have to rewrite sentences over and over to get them exactly right. And your ideas won't just be imprecise, but incomplete too. Half the ideas that end up in an essay will be ones you thought of while you were writing it. Indeed, that's why I write them.

Once you publish something, the convention is that whatever you wrote was what you thought before you wrote it. These were your ideas, and now you've expressed them. But you know this isn't true. You know that putting your ideas into words changed them. And not just the ideas you published. Presumably there were others that turned out to be too broken to fix, and those you discarded instead.

It's not just having to commit your ideas to specific words that makes writing so exacting. The real test is reading what you've written. You have to pretend to be a neutral reader who knows nothing of what's in your head, only what you wrote. When he reads what you wrote, does it seem correct? Does it seem complete? If you make an effort, you can read your writing as if you were a complete stranger, and when you do the news is usually bad. It takes me many cycles before I can get an essay past the stranger. But the stranger is rational, so you always can, if you ask him what he needs. If he's not satisfied because you failed to mention x or didn't qualify some sentence sufficiently, then you mention x or add more qualifications. Happy now? It may cost you some nice sentences, but you have to resign yourself to that. You just have to make them as good as you can and still satisfy the stranger.

This much, I assume, won't be that controversial. I think it will accord with the experience of anyone who has tried to write about anything non-trivial. There may exist people whose thoughts are so perfectly formed that they just flow straight into words. But I've never known anyone who could do this, and if I met someone who said they could, it would seem evidence of their limitations rather than their ability. Indeed, this is a trope in movies: the guy who claims to have a plan for doing some difficult thing, and who when questioned further, taps his head and says "It's all up here." Everyone watching the movie knows what that means. At best the plan is vague and incomplete. Very likely there's some undiscovered flaw that invalidates it completely. At best it's a plan for a plan.

In precisely defined domains it's possible to form complete ideas in your head. People can play chess in their heads, for example. And mathematicians can do some amount of math in their heads, though they don't seem to feel sure of a proof over a certain length till they write it down. But this only seems possible with ideas you can express in a formal language. [1] Arguably what such people are doing is putting ideas into words in their heads. I can to some extent write essays in my head. I'll sometimes think of a paragraph while walking or lying in bed that survives nearly unchanged in the final version. But really I'm writing when I do this. I'm doing the mental part of writing; my fingers just aren't moving as I do it. [2]

You can know a great deal about something without writing about it. Can you ever know so much that you wouldn't learn more from trying to explain what you know? I don't think so. I've written about at least two subjects I know well — Lisp hacking and startups — and in both cases I learned a lot from writing about them. In both cases there were things I didn't consciously realize till I had to explain them. And I don't think my experience was anomalous. A great deal of knowledge is unconscious, and experts have if anything a higher proportion of unconscious knowledge than beginners.

I'm not saying that writing is the best way to explore all ideas. If you have ideas about architecture, presumably the best way to explore them is to build actual buildings. What I'm saying is that however much you learn from exploring ideas in other ways, you'll still learn new things from writing about them.

Putting ideas into words doesn't have to mean writing, of course. You can also do it the old way, by talking. But in my experience, writing is the stricter test. You have to commit to a single, optimal sequence of words. Less can go unsaid when you don't have tone of voice to carry meaning. And you can focus in a way that would seem excessive in conversation. I'll often spend 2 weeks on an essay and reread drafts 50 times. If you did that in conversation it would seem evidence of some kind of mental disorder. If you're lazy, of course, writing and talking are equally useless. But if you want to push yourself to get things right, writing is the steeper hill. [3]

The reason I've spent so long establishing this rather obvious point is that it leads to another that many people will find shocking. If writing down your ideas always makes them more precise and more complete, then no one who hasn't written about a topic has fully formed ideas about it. And someone who never writes has no fully formed ideas about anything non-trivial.

It feels to them as if they do, especially if they're not in the habit of critically examining their own thinking. Ideas can feel complete. It's only when you try to put them into words that you discover they're not. So if you never subject your ideas to that test, you'll not only never have fully formed ideas, but also never realize it.

Putting ideas into words is certainly no guarantee that they'll be right. Far from it. But though it's not a sufficient condition, it is a necessary one.

What You Can't Say

January 2004

Have you ever seen an old photo of yourself and been embarrassed at the way you looked? Did we actually dress like that? We did. And we had no idea how silly we looked. It's the nature of fashion to be invisible, in the same way the movement of the earth is invisible to all of us riding on it.

What scares me is that there are moral fashions too. They're just as arbitrary, and just as invisible to most people. But they're much more dangerous. Fashion is mistaken for good design; moral fashion is mistaken for good. Dressing oddly gets you laughed at. Violating moral fashions can get you fired, ostracized, imprisoned, or even killed.

If you could travel back in a time machine, one thing would be true no matter where you went: you'd have to watch what you said. Opinions we consider harmless could have gotten you in big trouble. I've already said at least one thing that would have gotten me in big trouble in most of Europe in the seventeenth century, and did get Galileo in big trouble when he said it — that the earth moves. [1]

It seems to be a constant throughout history: In every period, people believed things that were just ridiculous, and believed them so strongly that you would have gotten in terrible trouble for saying otherwise.

Is our time any different? To anyone who has read any amount of history, the answer is almost certainly no. It would be a remarkable coincidence if ours were the first era to get everything just right.

It's tantalizing to think we believe things that people in the future will find ridiculous. What would someone coming back to visit us in a time machine have to be careful not to say? That's what I want to study here. But I want to do more than just shock everyone with the heresy du jour. I want to find general recipes for discovering what you can't say, in any era.

Directional Nudges

Directional nudge - nuanced & less clickbait

Write out the content again but this time:

Increase the nuance of your description of the topic by 20%.

Decrease the “clickbait”, “common patterns of speech” by 20%.

Make sure to stay in line of all previous instructions

Directional nudge - simplify sentences and terminology

Write out the content again but this time:

Increase the simplicity and activeness of your sentence structures by 10%.

Decrease the “jargon”, complex terminology and “adverbs” by 20%.

Make sure to stay in line of all previous instructions

Discussion on Style guides

Style guides are tricky. LLMs follow patterns and we are trying to describe a set of patterns and have the LLM follow them. But describing /= showing. The following rules will help considerably.

Best option: Provide examples of what you want. Show it your style. Have it emulate.

Next Best: Provide specific rules. For example “Never use the following words....”. You can use this strategy to enforce a different style that does not sound like an LLM. “Every question should come in pairs.”

Meh option: Describe what you want. For example: “sound clear and refined.” The problem with this is that language is too high dimensional to describe in this manner. It will default to “the average” within the bounds of “clear and refined”.

BUT honestly all these together are BEST IMO @At_moon_what_now THEN add directional nudges.

It never gets it first shot - the directional nudges are the final icing on the cake which makes it work. You need to let it make the mistakes and then push it in the the direction you want.

Keep in mind: if you say certain words “email, social media, etc.” These words will drastically effect the style guide because the patterns within those contexts are “stronger” than the style guide.

Hot comments

about anything